Follow the links in the box below to travel quickly to particular points of interest on the route. Places of particular interest mention in the text are highlighted in blue.

Click here to see a more detailed map of the complete circular route the bus travels (opens in a new window).

Via C Battisti to Via Nazionale

Via S Stefano Rotondo to the Colosseum

North-South Route

Bus 117, during the working week, has a pair of complementary, almost circular routes (when taken together), one starting and the other finishing at Piazza del Popolo. If you are intending to travel in its North-South direction, it would be wise to begin your journey here at this beautiful square (described elsewhere in'The Obelisk Trail' amongst other tours available on this site). This is because on the first part of the trip at least, the bus is always very crowded, and boarding the bus at the Capolinea is about the only way to ensure that you get a seat; even so, you may have to take the bus waiting to leave second-in-line! It is not unusual to find even the standing-room completely packed out. Fortunately they leave every 10 minutes or so, so you can at least admire the scenery around the Piazza while you are waiting, and maybe even nip into one of the 'twin churches' at the top of the Corso if they happen to be open - a rare event, especially with S Maria in Montesanto, the one on the left as you look down towards the city-centre: so if it is, carpe diem!

The first mile or so of the route gives you a wonderful chance to travel the entire length of this famous road, once the ancient Via Flaminia, which continued on through the gate out of the city behind you to the north. It was first constructed in 221 BC, and was renowned for its breadth as well as its straight length, especially at the southern end where it went by the name of Via Lata ('Broad Street'). Up here towards the gate in the city wall, the district itself was very rural, covered with groves and meadows: apart from a few nearby villas on the ridges owned by the super-rich such as Lucullus or Pompey, it would be many centuries before habitation crept up this far. In the Middle Ages, the great riderless horse-race, from which the street takes its current name, was instigated by Pope Paul II, creating intense rivalry between the inhabitants of the competing 'rioni'; something very similar can still be seen in the famous "Palio", held twice a year in Siena. This chaotic spectacle continued right up until it was finally discontinued in the 19thcentury.

Nowadays it is still pretty chaotic - but this is due instead to the frantic Roman traffic, particularly at the southern end; and almost equally at the top stretch where although motor vehicles are banned (except for our bus!) there are hoards of pedestrians indulging in the traditional 'passeggiata'. In the late afternoon during the week and at almost any time at weekends it is practically impossible to walk peacefully down the street without continually having to dodge other people; somehow, though, this all seems to add to its character!

When the bus starts (number 119 also travels the same route as far as Piazza Venezia, so make sure you are on the right one), cast a quick eye to the left: you will see one of the sets of bike-sharing hire-docks, which can be another interesting way to see the city, although the combination of homicidal motorists, bumpy cobbled streets and hills (you'll soon discover there are far more than seven, believe me!) make it not quite such a relaxing option as one might think. There are about 25 of these stalls at various spots around the city (compare that to the 300 or so in London and draw your own conclusions…)

Shortly after this, still on the left, a pair of red flags announces the site of the Casa di Goethe, the lodgings of the great poet during his time in Rome, now a small museum and library.

Directly opposite is the Palazzo Rondinini-Sanseverino, now a branch of the Bank of Siena; this wonderful old family pile is usually one of the set of privately- or corporately-owned palaces which open their doors annually to visitors on the first Sunday in October, in a lovely idea called the 'Invito a Palazzo'. This particular building contains a beautiful courtyard crowded with ancient marbles - well worth seeing if you happen to be in the city on the right day.

The gradually lengthening small streets branching off either side of the Corso (to join the other two roads which make up the 'Tridente' of the district's name) include Via Angelo Brunetti and Via del Vantaggio (right), with a couple of decent restaurants, and on the left the tiny Via della Fontanella, Via Laurina, and just before its eponymous church, Via di Gesu e Maria. The church itself is typically Baroque, with architecture inside and out by Rainaldi. The interior is surprisingly spacious and brightly decorated.

Practically opposite is another church, dedicated to S Giacomo. It is known by two additional sobriquets: sometimes "…degli Incurabili", referring to the adjacent hospital, originally for plague-victims: there is today a convenient and friendly Chemist's shop just before it on the Corso! Its other name is "…in Augusta": close by, as we shall shortly glimpse round the corner of a turning not far ahead, there stand the woebegone remains of the Mausoleum of Augustus.

Alongside the church of S Giacomo runs Via Canova, which has walls embedded with decorative stonework from classical and later times (it is of course named after the famous sculptor).

Also next to the church is the first of the 4 (request) bus-stops down the street; no-one is very likely to get off, unfortunately, but one or two more may try to squeeze on: quite possibly one of them will be me, as this stop stands opposite the Hotel Mozart, on the corner of Via dei Greci, which is where I invariably stay on my shorter visits to the city!

If you look hard down the street next-but-one on the right (Via dei Pontefici), you may just make out the squat husk of Augustus's Mausoleum. The whole area around it has been under excavation for years; hopefully one day they will eventually decide how to restore it.

The street opens up into the Piazza di Augusto Imperatore, completely redesigned with clunky rectangular Fascist architecture by Mussolini - rumour had it that he was intending to have his own remains interred with those of Augustus and his family in the central chamber of the tomb.

Between Via dei Greci and the next street on the left, Via Vittoria, the block (at least, the part behind the shops and bars - Caffé Maneschi is quite a good one) is taken up by the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia (see 'Respighi's Rome'), which has entrances on both streets. Via Vittoria also has a useful small supermarket.

Next on the left is Via della Croce, a popular and lovely cobbled street lined with cafés and restaurants, many worth a try (see 'Talking Statues').

The road now widens (temporarily) to make room for the wide terrace in front of the church of SS Ambrogio e Carlo, a very large affair with unusual black-and-white horizontally striped nave-pillars. It has one of the largest domes in the city, but otherwise is rather disappointing inside; one point of interest perhaps is a chapel dedicated to St Olav, the patron saint of Norway! Outside it, the terrace is a favourite sitting spot for youngsters, and at weekends there is frequently a street-show of some type going on there (to add to the congestion).

Just past it is the next bus-stop, placed here really to serve the streets radiating from Largo Goldoni (named after the eighteenth century playwright); this is a big road-junction, which from this point on allows other traffic to join in the fun down the Corso (still only one-way fortunately). Opposite on the left you should get a fine view of the Spanish Steps at the end of Via Condotti, legendary as the smartest shopping street in the city. The whole area around the Piazza di Spagna is famous for its expensive designer shops, but in this particular street your jaw is likely to drop further than usual at the price-tags. For mention of some other, perhaps more edifying places it also contains, see 'Talking Statues'; at the bottom end is a little church also with Spanish connections: SS Trinita dei Spagnoli.

The large block on your right now is the Palazzo Ruspoli; since it was sold into public hands (currently owned by the Memmo Foundation) it now holds interesting temporary exhibitions of paintings or photography.

A wider, pedestrianised piazza opens up beyond it, home to the ancient church of S Lorenzo in Lucina (under restoration in 2011). This was one of the original 'titular' churches (and will be described more fully in another of the walking tours); one of its points of interest is the tomb of the great French painter Poussin.

Also in the piazza at the far end stands the café-restaurant Ciampini, which is quite well-known, especially for its gelati.

After it, still on the right, comes Palazzo Fiano, perhaps most interesting for having been built over the original site of the extraordinary Ara Pacis, erected by Augustus as a huge publicity display; this has now been moved and re-sited next to his Mausoleum. During the attempts to retrieve this wonderful monument, the entire excavation area beneath the palace had to be deep-frozen to prevent its collapse into the unstable ground - one of Mussolini's architects' more remarkable achievements!

On the opposite side, the Via Frattina is the last of the pretty pedestrian streets leading off to the left in the direction of Piazza di Spagna. Its name commemorates the wooded groves ("fratte") which were still in existence here even in the seventeenth century, also giving the church of S Andrea delle Fratte, at the further end, its name. With traffic from here on becoming a free-for-all, it is amazing to think how the area has changed so much in such a relatively short time with the creeping expansion of the city centre. It is still possible to find a small remnant of leafy tranquillity, however, in the pretty cloisters of the church.

The bus now enters what is really the modern political heartland. To the left, in Piazza del Parlamento, you can see the back of Rome's Lower House, the Chamber of Deputies: Palazzo Montecitorio. Its front is more remarkable (see 'The Obelisk Trail'), but unfortunately invisible from the bus.

Just after the piazza, there is another request bus-stop, which should by now see a few of your fellow travellers getting off. Meanwhile on the left, past a couple of smaller streets leading to the Piazza di S Silvestro (as well as containing the main Post Office and the English Catholic church of that name, the piazza is largely a bus terminus - but currently out of commission in Oct 2011 for reconstruction), we reach Largo Chigi, the nearer end of what will become the busy Via del Tritone.

At the corner of the junction, on the left, is the capital's branch of the well-known department store 'La Rinascente'; on the right is the very grand-looking shopping arcade called the Galleria Colonna (named after the square we are about to reach opposite, and nothing to do with the art-collection of the Palazzo Colonna nearer the city-centre!). This Y-shaped mall has a pleasant café, and its air-conditioned corridors can be a welcome refuge for a pit-stop on a hot day.

An interesting way to get across the road between the two is to go underground, through a subterranean bookshop, which agreeably goes by the name of 'Libreria M. T. Cicerone'!

On the right now as the bus continues is Piazza Colonna, containing Rome's "other" column - that dedicated to Marcus Aurelius. As remarked on one of the other bus-tours which passes this way, this monument may not have the finesse of its sister 'Trajan's Column' at the end of Via dei Fori Imperiali, but it is a great shame that few visitors to Rome realise it even exists.

The 3 sides of this huge square are each very interesting: apart from the column itself and the attractive pale-pink marble fountain in front of it, Palazzo Chigi on the right is the official residence of the Prime Minister (whoever that may be at the moment…); at the back (Palazzo Wedekind) are the offices of the newspaper 'Il Tempo'; and on the left, as well as another good bar (amazingly cheap, too, given that it's practically the PM's local) is a tiny church dedicated to SS Bartolomei ed Alessandro dei Bergamaschi - it is rarely open, but a Saturday afternoon Mass service is usually full - all 24 or so of the celebrants no doubt praying fervently for the wisdom of their masters opposite. For a bit more on this area see 'A Ride on Bus 116'.

The Corso starts to narrow again between the dark, high façades of the palaces on either side. Although there are a few small shops and cafés, the buildings are mainly offices, banks and hotels for the next few blocks; on the ground floor of one of them (right) is an exhibition hall called the Museo del Corso. Especially if you are on foot negotiating the extremely narrow pavements, it can seem rather oppressive. The side-streets however lead off to some interesting places.

On the left, a couple of streets (Via dei Sabini and Via delle Muratte) both lead to the Trevi Fountain (see'Respighi's Rome'); meanwhile on the right the Via di Pietra heads towards the Pantheon, via the impressive columns of the original Temple of Hadrian, used to form one side of a finance building; another a little further down (Via della Caravita) takes you in the same direction, but this time you pass the Jesuit church of S Ignazio set in its own delightfully theatrical little piazza (see 'A Ride on Bus 116'). Piazza Navona is only 7 or 8 minutes walk away if you take either road.

At this junction also is the final bus-stop on the Corso (travelling in this direction at least); there is still a good way to go, and I have known travellers taken rather by surprise that they can't get off further down until the bus is well out into Piazza Venezia - don't get caught out!

On the right next is a street leading towards the Collegio Romano, now simply a state high-school; on the left, set back from the road, is the church of S Marcello, a very ancient foundation originally. It was first begun in the fourth century in honour of the third Pope, Marcellus I, who is said to have been set to work here by the emperor Maxentius in what was apparently then a stopping point for the Roman Postal Service! Not actually all that far from the main office today… after devastating fires, however, it was eventually given the full Baroque treatment.

Down the very narrow and unprepossessing turning next on the left (Via dei SS Apostoli) can be found one of Rome's few attractions catering properly for children: 'Time Elevator' is a sort of interactive film-show, with moving seats and other surprises; amongst its presentations is a dramatised journey through the different ages of the city, meeting Julius Caesar, Michelangelo etc. It's worth looking for - you will probably have to search quite hard, as it is very poor at self-advertisement: there is scarcely even a sign outside until you are right upon it.

Opposite this street is the confusingly named Via Lata (this is a throwback to the Corso's original name - see above). Halfway down you might just glimpse a rather well-worn statue - this is one of Rome's six 'Talking' ones, called 'Il Facchino' - the Porter (see 'Talking Statues'). On the corner of this street you pass S Maria in Via Lata, another very early church, quite attractive inside; in the crypt beneath (which can be visited separately) are remains of ancient Roman store-houses (thought to be connected with the Saepta Julia) which were converted for use first by the early Christians possibly as a 'Diaconia' - originally this meant a place set up to dole out free food for the poor - and after that as a chapel. Spanning the street here was once an arch built in honour of Diocletian - ironically one of the severest persecutors of the faith.

The palace on the left, more forbidding-looking than most, is Palazzo Odescalchi, designed to imitate the Florentine palaces of earlier days. It has another long façade facing the Piazza SS Apostoli parallel behind, and would probably have been rather more attractive in the days before the Corso became choked with traffic and the resultant corrosive, blackening fumes. Its next-door-neighbour, Palazzo Salviati, was designed by Rainaldi in the 1660's.

Opposite them both however is possibly the jewel of the whole street, the Palazzo Doria-Pamphilj (try to catch a glimpse of its courtyard through the main entrance as you pass). This is home not only to the current prince Jonathan (actually parts of it are also rented out to tenants), but also to his wonderful family art collection, open to the public; some of the family's state rooms can also be visited. For more details - this really is one you should come back and visit if you can - see 'A Ride on Bus 116'.

Surrounded on the two inward sides by this palace (the Vicolo Doria separates them), but forming in fact the bottom right corner of the Corso as it emerges onto Piazza Venezia, is the Palazzo Bonaparte, where Napoleon's mother (herself an Italian) spent her final years.

We have taken quite a long time describing the journey down the Corso, but to be fair it is the most built-up part of the route, with always something remarkable to see. Since the bus is very likely to be grinding to a halt pretty frequently as well, this should at least give you something to look at! There are still plenty of delights to come, but they are rather more spread out.

The 117 now launches out into Piazza Venezia, and travels practically the whole way round it. If you are doing the trip in the morning or the evening rush-hours, you may well be treated to a performance from one of the city's most theatrical officers-in-uniform: standing on a retractable pillar facing the Corso is likely to be one of the traffic police, conducting the cars like an orchestra to the accompaniment of his whistle (and their horns). Presumably auditions are held to ensure they appoint someone with enough of the 'Maestro-factor' about him!

The first stop is beside the Palazzo Venezia, once used by Mussolini for his offices, and now a museum of some of the more unusual types of item - militaria, fine china and jewellery, etc. Other dedicated exhibitions are frequently held here, and even just a view of the courtyard is worthwhile if you happen to be walking past (the main entrance is round behind to the right).

The piazza of course takes its name from this striking building, as well as the general association of the area with Venice itself thanks to the Basilica of S Marco a little further to the right. It is generally reckoned to be the 'city centre', and is definitely the largest open piazza (although it does sprawl into extra corners we won't be visiting today). There may be excavations still going on to continue with the construction of Metro Line C which is meant to have a station here (if the work is ever finished); this will at least be one of the more useful stops on the lines. The whole expanse was widened even further into what we see today when the square was redesigned to make room for the monument described below; this involved actually 'picking up' and moving one of the adjacent buildings 'a bit to the left' - Basil Fawlty would've been proud of them! Mussolini too was able to make the most of it: it meant he could deliver speeches to a suitably large crowd from the balcony of the palace.

The bus next travels along the front of the Monument to King Vittorio Emanuele II, otherwise known as the Altar of the Nation, the Wedding Cake, the Typewriter…and by progressively even less flattering nicknames!

It was constructed at the end of the nineteenth century to celebrate the unification of Italy (under the existing royal dynasty of Savoy - hence V. Emanuele's strange "the second" title as Rome's first King since Tarquinius Superbus was expelled in the 5th century BC). The gigantic design in blisteringly white Brescian marble is often criticised for being badly at odds with Rome's native light-absorbing travertine; it also involved a drastic reshaping of this side of the Capitoline Hill and its northern slopes.

But for all its kitsch 'out-of-placeness', I confess that after 30 years or so the monster is beginning to grow on me. Quite apart from the excellent terrace café-bar (with some of the friendliest baristas in the city), and the magnificent views across the city from its various levels - it even has a panoramic lift right to the top - there is something quite grand, certainly dramatic about it. Kaiser Wilhelm had his tongue no doubt rather firmly in his cheek when he described it originally as "the ultimate manifestation of Latin genius", but let's face it, where its building programme was concerned Rome was never a city to do things by halves!

More detailed guide-books will give you information about the mysteries it conceals within (including a museum of the Risorgimento, and collections of flags and medals) - not to mention the story of the meal for over 20 guests served inside the huge equestrian statue of the King himself to celebrate its inauguration.

For now, as you pass, you can admire the modern successors of the Vestal Virgins: a couple of smartly-uniformed soldiers on guard over the ever-lasting flame in the brazier at the front.

Stretching past it to the right is Mussolini's Via dei Fori Imperiali (described elsewhere), leading to the Colosseum; but the 117 continues back around the third side of the piazza in the direction of the Corso again. Travellers who have got on the bus because it is advertised as going to the Colosseum are often disconcerted by this - you may be able to reassure them that it will get there, eventually; but it has a few twists and turns to complete first - including at last the first of its visits to the actual Subura!

As the bus turns back apparently towards the Corso again, you can get a good view of Trajan's Column at the rear of his magnificent forum and market-complex, the main entrance for which we are about to pass. Just this side of it are the churches of S Maria di Loreto and S Nome di Maria - almost another pair of 'twin churches' at the bottom end of the Corso! The other buildings on this side of the piazza are of less interest (mainly offices).

Just when you are beginning to think that the driver has decided to cut his (or her) losses and make an early return to base, the bus heads round to the right, along Via Cesare Battisti. Opposite on the left is Rome's small and quirky Wax Museum. In a window outside there is a constantly revolving platform with effigies of both the John Paul popes - time your photograph right, and as they turn you can get yourself snapped having your own personal audience…

The road turns sharp right, opposite Via della Pilotta - a charming street with an attractive set of bridge-walkways crossing above it; sadly these are only for the use of the Colonna family: they are designed to connect their palace on the left with its spacious private gardens.

Following the slope of the Quirinal Hill,you now begin to climb the road (now called Via Quattro Novembre). If you look to the right, notice the facades of two very contrasting buildings (the Torre Colonna & Casa Rubboli at numbers 100-102).

On both sides of the road you can see sets of steps leading up and down the side of the hill; the ones on the right give views firstly down into Piazza Venezia again, and later, at the turn at the top, down to Trajan's Column; those on the left lead up to the Quirinale.

Continuing to zig-zag, the bus passes the main entrance to Trajan's Markets (well worth a visit - a future tour will describe them) and reaches an island in the road where you can see remains of the early Servian Wall.

This is Largo Magnanapoli; it features as a key hub in the walking version of this tour, as a couple of the roads leading from it are particularly associated with the ancient Subura, especially Via Panisperna straight ahead. Also high straight in front of you is the small walled park, called Villa Aldobrandini (see 'The Obelisk Trail').

The attractive church to the right, raised up with a double white staircase is dedicated to S Caterina da Siena (distinguished from another one in the city also dedicated to the saint on Via Giulia by the extra title ' a Magnanapoli'). It is unfortunately not easy to find it open.

If the bus has to stop at the lights (as is more than likely), ahead of you is another view up to the top of the Quirinal Hill: you can just about get a glimpse of the obelisk in the distance, in front of the Presidential Palace.

Previously, the bus used to climb the Viminal Hill, heading towards Termini Station along the Via Nazionale. Now however, it turns down Via Panisperna for a short distance, before resuming its old route with a right turn down Via dei Serpenti.

This long straight road descends into the very heart of the Subura. It has a wonderful view of the Colosseum straight ahead (as yet, another red herring!) in a vista which has quite possibly not changed since ancient times. The emperor Vespasian was very astute in the wider design of his greatest public work. The common people whose homes had mostly been destroyed in the Great Fire of AD 64 had then seen Nero appropriate for his own private use vast swathes across the city: their new emperor understood how much they needed this massive morale-booster - and, equally importantly, needed to be able to see it going up!

This area at the bottom of Via dei Serpenti, where it is crossed by Via della Madonna dei Monti/Via Leonina, Via Baccina and others, was the centre of the poorer part of the city, known as the Subura (or often, 'Suburra'). The name is regularly thought to be from a root similar to our own 'suburbs', but this is by no means certain, and it is even possible that the way the name was written and how it was actually pronounced were completely different (the ancient authority on language Quintilian mentions this anomaly, giving the original written spelling as something like 'Sucusa'). Possibly again there is some old connection with the regular fires that broke out amongst the crowded and rickety tenement blocks that were the a poor man's general abode: there is a Latin verb with spellings including the stems 'subur---' and 'subust---', which has a connection with our word 'combust-ion' etc. The short answer is that no-one really knows where the name came from!

What is well-known is that it was generally pretty notorious as the 'red-light' district in the city: dirty, noisy ('clamosa', says Martial) and crowded ('fervens' - Juvenal's word, which has lovely wide connotations such as 'seething, boiling' - generally chaotic!)

On its way down the bus passes some small but interesting shops (characteristic of the modern area now), and crosses junctions with the previously mentioned Via Panisperna and Via Baccina before reaching a lovely little opening on the left with a couple of small trattorie clustered around a fountain; there are always locals sitting beside this reading the newspapers or chatting.

Just past this on the right is the local church of the Madonna dei Monti (the modern name of the rione), on a street named after it which is nothing less than the ancient Argiletum, the famous road leading to and from the Forum. The walking tour will explore this road in more detail - its continuation across to the left (Via Leonina) culminates in the 'Piazza della Suburra' itself, right next to the Cavour Metro station!

The 'Monti' region is today one of Rome's up-and-coming districts, often sought after by those looking for a trendy place for an apartment. Its local streets provide a wealth of unspoiled and exciting shops (including Rome's best chocolatier). Whether the tenants of the second or third-floor flats nowadays give much thought to the area's old reputation for seedy brothels and ramshackle tenements is unclear - in those days, the higher the apartment, the poorer the occupant invariably was: consider the question of a water supply! Its vivid descriptions by the poets like Juvenal and Martial give a great flavour of its past persona: for example, how people die from lack of sleep, thanks to the carts clattering around because they are forbidden to travel in daylight; and one of Juvenal's 'Satires' has a lovely passage about the risks you take trying to get home through the dark and dangerous streets at night - don't go out without first making your will! Modern seekers after street-cred however are by no means the first to throw in their lot with the 'plebs': even Julius Caesar is said to have lived in a pad here once - no better way to get the feel of what the ordinary people were saying and thinking, and this must have been a key spur to his popularist agenda in later years.

The bus will be back to visit some of the rest of the neighbourhood on its return route; for now it turns right, onto Via Cavour, one of Rome's busiest and least attractive traffic arteries. It was built in 1890, destroying in the process many old streets and buildings that had survived since the Middle Ages, and now carves its way through the dip of the old Subura between two spurs of the Esquiline Hill. It takes its name from the political hero of the Risorgimento (he also has a huge piazza named after him near Castel Sant'Angelo on the other side of the river). At its upper end, it is close to Termini and S Maria Maggiore.

Roads leading up out of the Subura to the East wound up the hill towards the Esquiline gate, just outside which stood Rome's main cemetery; on the way they met at a monumental fountain, which was probably situated in the piazza behind S Martino ai Monti; the ruined structure that stands today in the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele is another possible candidate for this, but that one was built later, in the time of Alexander Severus. For the use of the people, along the way Augustus built a large market, with a portico named in honour of his wife Livia. Estates beside this road had previously been home to expensive villas belonging to Pompey and Marc Antony; Augustus's friend, the great literary patron Maecenas also owned a vast tract of land here (all this district is explored in the walking route).

We soon reach the bottom end of Via Cavour, where it meets the Via dei Fori Imperiali, leading from Piazza Venezia back to the right. The ruined tower at the foot of the junction (also on the right) is known as the Torre dei Conti (a fortification belonging to one of the innumerable warring noble families of the Middle Ages). You may just see, further past it a better preserved example, the Torre delle Milizie; several earthquakes were responsible for the partial collapse of the nearer tower, and it was then not short of developers to plunder its stonework.

By now you may have been despairing of ever reaching the Colosseum; but at this point the bus turns left to head at last genuinely towards it, along the side of the original Forum on the right (its main modern entrance is here, at the bus's first stop). Look up at the high wall as you pass along: the stone maps showing the extent of the empire at various dates are interesting, and neatly done.

No doubt many of your fellow travellers will disembark at the next stop (it is also very convenient for the Metro station, one of the very few that stands at all close to any of the big 'attractions'). The Colosseum is described in detail elsewhere, since this is not the main target of this tour; even so, you still have a perfect opportunity to admire this side of the exterior, the best preserved part of its extraordinary stone shell. Spot if you can the 4 different 'orders' of its pillars - Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and a topmost level of a sort of composite design.

The never-ending throb of traffic that streams past (one side nowadays is at least spared) cannot help but take its toll on the structure; most obvious of course is the blackening due to pollution, but we can only guess at the strain the constant vibration is putting on the foundations. It is a tribute to Vespasian's architects, with their skill in draining Nero's artificial lake and then stabilising the ground to support its massive weight that this most iconic symbol of Imperial Rome is still standing at all.

The bus travels on along Via Labicana. Look to your right just past the traffic lights at the first wide junction: the half-sunken masonry there is part of what remains of the gladiators' training school, known as the Ludus Magnus. The majority of it is still buried beneath the modern streets, but from a closer inspection you can make out half of a semi-circular wall, which would have contained their 'practice' arena. Smaller private shows were sometimes held here: Titus, who oversaw the completion and opening of his father's amphitheatre, was notorious for his obsession with watching contests to the death.

To the left, the Oppian spur of the Esquiline Hill rises steeply; it contains two sets of important ruins, one on top of the other. The visible remains - massive exhedra walls and apses - are part of the huge bath complex built by Trajan at the beginning of the second century.

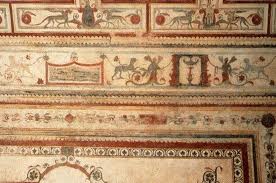

While the fields were being worked in the 1400's, someone broke into underground caves ('grottoes'). They found beautiful Classical frescoes decorating an enormous set of rooms: no less than the fabled Golden House of Nero. Copying and imitating these pictures, artists (such as Raphael himself, who was lowered down into the chambers on ropes) produced work in the style which became known as 'Grotesque' after the grottoes where the pictures had been found. Trajan had used his hated predecessor's enormous private palace as the foundations for his public bequest, just as Vespasian had done when building the Colosseum.

Although you can wander around the ruins of the Baths at will, the rooms below which have been open intermittently for visits to the Domus Aurea are currently closed once again for stabilisation. If they should ever re-open, you will probably be required to book visits in advance - although, to be honest, judging from past experience, the rather confusing and not very extensive area you are likely to be shown is a bit of an anti-climax compared with what its grandiose name might have led you to expect.

The bus now turns right. Already visible from Via Labicana, and making a striking contrast with the gruesome modern glass-fronted block of offices that precedes it, is the wonderful multi-layered Basilica of S Clemente, one of the most fascinating buildings in the entire city. See the 'Vir in Via' tour entitled 'Saints and Martyrs' for an attempt to do justice to this ancient foundation and its surrounding area - an amazingly rural and evocative throwback to the quiet landscapes which characterised the outskirts of the early city, compared with the uniform modern soulless sprawl to be found stretching out to the suburbs nowadays. Briefly as you pass for now, try to peer in at the entrance of the walled quadroporticus which contains a lovely little fountain surrounded by cobbles.

The church itself, in the care of Irish Dominican friars, holds many treasures, including a remarkable extensive carved choir screen, and some frescoes from the earliest days of the Renaissance by Masolino and his pupil Masaccio.

Even more remarkable is the series of lower levels beneath the main building. Firstly you can visit a much earlier lower church, discovered by the Irish priest Father Mullooly during restoration work in the 1860's; here there are (now very faded) remains of some very ancient Christian wall-art; below this there is a level from Classical Roman times, with an almost intact Mithraeum; take a few steps lower and you are walking at the original street level, between the walls of some Roman insulae, where you can search out the source of a distantly audible underground stream.

At the road junction, look up the street ahead: to the left you may just see the back of another beautiful ancient building: the church of SS Quattro Coronati is not visible again from the bus on this trip, but the walking-tour mentioned above will also take you to its peaceful courtyards and cloisters.

Instead, the bus turns left, and climbs one of the least remarkable stretches of its journey; but the name of the street gives you more than a clue about what lies ahead: you are approaching the end of the line (in this direction) where Via di S Giovanni in Laterano meets the wide piazza of the same name in front of the Lateran Basilica, the true cathedral of Rome.

The bus emerges at this big traffic junction, past a couple of roads leading back to the right - one to SS Quattro Coronati again, the other soon to be our route back. It swings round to the right and pulls into its temporary resting place; probably there will be at least one other waiting to leave there already, so if you want to continue the tour straight away, you can just change buses now - you won't have more than 7 or 8 minutes to wait.

On the other hand, you could visit the Basilica first….!

South/North Route

While you are waiting for the bus to leave, there is plenty to look at around you. The Basilica of S Giovanni almost needs a tour to itself and will be described elsewhere; for some information on the stately red-granite obelisk, see 'The Obelisk Trail'. Here I will just mention a couple of points of interest which you can at least see from where you are.

To the far left, behind the Lateran Palace which forms the longer side of the 'L'-shaped complex and was once the residence of the Popes themselves, is a building containing several relics from an earlier version of the palace, now destroyed. A true destination of pilgrimage for the faithful, it holds the Scala Sancta (or 'Holy Staircase') brought back from Jerusalem by Helena, the mother of Constantine, who believed it to be the very structure Christ had descended after his judgement by Pontius Pilate. Pilgrims today may only ascend or descend it on their knees. At the top, (although it is can never be visited) is the Sancta Sanctorum ('Holy of Holies') - the Pope's private chapel.

To the right of the church is its octagonal Baptistery, the oldest such in Christendom and so the model for all the others built later. It has witnessed many great events of history, not least having been the place Cola di Rienzo spent the night (he used the ancient green porphyry baptismal basin as a bath) before announcing himself the Anointed Knight of the World…sadly for him, the beginning of his downfall (see 'Talking Statues').

When the bus begins its return journey, it travels briefly back the way it arrived into the square, but then takes the first fork to the left. To start with, this street is quite built up: it runs beside the Ospedale di S Giovanni, the main reception for emergencies in the city. Beneath it remains have been found of an early Imperial palace, belonging to the mother of Marcus Aurelius - appropriately, the equestrian statue representing her son which is now in the centre of the Piazza di Campidoglio once stood here in front of the Basilica.

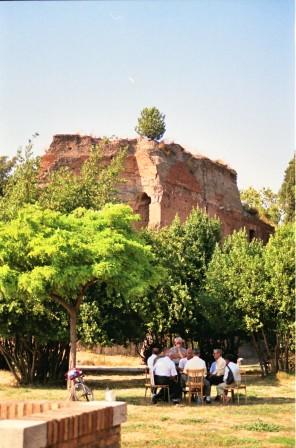

Soon the road becomes much quieter, almost like a country lane. On the right you travel along past substantial remains of the aqueduct of the Acqua Claudia. The road is named after the church you are about to pass on the left, S Stefano Rotondo. It is hard to get much of a view of this from the bus, but it is a remarkable old church, on a circular design, and quite a significant building amongst the city's early Christian foundations. For more information see 'The Obelisk Trail' or the walking tour 'Saints and Martyrs'.

After another short stretch, the road emerges onto a much wider street - but it's actually not usually very much busier. Look to your left to see another strut of the Claudian acqueduct, marooned separately in the middle of the road.

Behind it is the very attractive church of S Maria in Domnica, with a lovely fountain in front depicting a boat - the 'Navicella'. It is possible that there may be an obscure connection with the story of the Ark; certainly some of the very early ceiling decorations in the church seem to depict this Old Testament tale. Again, for a little more on this, as well as some information about the peaceful Villa Celimontana park behind the church, see 'The Obelisk Trail'.

The archway over the entrance to the narrow little alley on your left, next to the church of S Tommaso in Formis, is known as the Arch of Dolabella; it was really the Caelian Gate in the republican city wall. Down through it a pretty street called the 'Clivo di Scauro' leads towards the Circus Maximus.

The wide road you are now on, Via Claudia, descends back to the Colosseum. On the right, across the open park, is a military hospital; to the left, you travel past some very solid-looking remains of the outer surrounds of the Temple of Claudius. This was built originally by Nero to honour his stepfather - although it didn't take him long to incorporate it into his own Golden House after the great fire. The succeeding emperors restored it again to its earlier dedication.

By now, the Colosseum will once more be dominating the view ahead, with an added chance to see the Arch of Constantine standing to its left. This time you will get a good look at the south side, where a lot more work has been needed to shore up the partly-collapsed outer wall. The bus continues around the right-hand side of the amphitheatre; you will probably have to wait at the traffic junction crossing Via Labicana, so make the most of your chance to enjoy the view!

In fact, when you cross over onto Via Nicola Salvi (named after the main architect of the Trevi Fountain) you get an even more stunning view as the road slants upwards round to the left. This has to be one of the best vistas in the city.

To your right (if you can tear your eyes away) on this corner of the Oppian Hill is where the Baths of Titus stood - reclaimed for the public from Nero's private suite in the Domus Aurea. Nothing much now remains of them; however, they are commemorated in the name of the adjoining street and a trattoria on the corner. Here also is the first bus-stop since half-way down Via Claudia - I always think that it would be far more convenient to put in an extra one beside the Colosseum itself, at the central pull-in area which already exists for other buses just before the traffic junction…sadly, the authorities don't seem to agree; I suppose they think it would attract too many tourists for our small bus to cope with. Luckily for you, these notes can help you defeat their plans and show you where to get on and off it reasonably nearby anyway!

In any case, the bus continues round to the right, down through the gash of a deep valley between two raised streets on either side (the Via degli Annibaldi). The road on the right is named after the Fagutal, or 'Beech Grove', another of the four ridges of the Esquiline.

At the bottom, the bus crosses over Via Cavour, and enters Via dei Serpenti again - we are back in the Subura!

This time we will travel round it by a different route. Instead of making its return journey up Via dei Serpenti, the bus takes us right, into Via Leonina, and then straight away turns left, around the back of the little piazza with the fountain, from where it climbs Via del Boschetto.

There are again a lot of small and interesting shops along this road; the narrow street seems only just wide enough for the bus to rattle through - these drivers are very skilful! It takes you up to a T-junction with Via Panisperna, and turns right, travelling along this ancient street for a quarter-of-a-mile or so. The origin of the name is mysterious: one story has it based on the names of two prominent residents (Signori Panis & Perna!); more attractive is an idea that it is associated with the food 'dole' offered to the poor from one of the Diaconiae based here (possibly at S Lorenzo, where the bus is about to turn off). "Bread and Ham Street" is much more evocative!

If you can see ahead along the road, or briefly to your right in a moment when the bus swings round, you may just get a distant view of the Basilica of S Maria Maggiore, at the highest crown of the Esquiline Hill. Via Panisperna leads all the way to the wide piazza where it stands - although after Via Cavour was built, it assumed a new 'alias' for its final stretch (see, for an extra mention, 'The Obelisk Trail'; the walking version of this current tour takes you up closer, but by a different route.)

For now, though, the bus turns left into Via Milano. Just at the junction, set back up to the right in a little open square at the top of a stairway, is the pretty church of S Lorenzo in Panisperna; there is a stop for the bus just a short way onto Via Milano if you want to explore the Subura further - even on the walking tour it can save a bit of energy to take the bus along this last uphill stretch from Via dei Serpenti.

Via Milano leads down the hill again (really the slope of the Viminal Hill by now) to a crossroads with the main artery Via Nazionale. It goes straight over, and then descends underground for a few hundred yards into an underpass which runs right beneath the Presidential Palace on the Quirinal Hill. It emerges on Via del Traforo, to another main junction, this time with Via del Tritone, and crosses over at the lights into Via dei Due Macelli.

From this point on, it takes the same route as two of the other little electric buses; number 119, the rest of whose journey to the terminus it shares exactly; and number 116, which goes as far as Largo Mignanelli, just at the southern end of the extended stretch of Piazza di Spagna, before somewhat confusingly heading off to rather more distant parts (see 'Another Ride on Bus 116', available on request).

The journey up to and including Piazza di Spagna and the Spanish Steps is described elsewhere, so it would be pointless simply repeating it all here; from the far end of Spagna up to Piazza del Popolo, likewise, you can find an account within 'Respighi's Rome'. I will shamelessly abandon you to go and look at those pages!

I hope that this perhaps rather misnamed itinerary will have given you a 'taste', if not actually a 'smell' of the Subura, amongst all its other twists and turns; the full experience can only really be achieved on foot, however. As mentioned earlier, one of the walking tours within 'Vir in Via' is intended to cover it in much more detail - and I hope too that you will find other itineraries around the city to interest you amongst the pages of that section of this website. Please consult this link to view some of the up-coming tours; I am intending to add more descriptions periodically.