If you already know and enjoy the music of Respighi, you'll understand why I've written these tours.

If you don't know his music, but love Rome, I will be surprised if after listening to the pieces linked to these tours you decide you don't enjoy them!

If you do know his music, but don't enjoy it…maybe getting a little deeper into it with these notes as a prompt may change your mind….

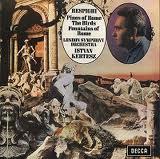

My favourite recordings of the pieces:

'Pines…' and 'Fountains of Rome' - London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Istvan Kertesz (available on a Decca CD also including 'The Birds')

'Roman Festivals' - Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Eugene Ormandy (SONY classic CD - has the other two pieces as well, but I prefer Kertesz's versions!)

N.B. Any references to timing points in the music are based around these performances, but other recordings are available….(the timings should still be close enough!)

Click within the box below to travel quickly to the different sections of the page.

I honestly believe that anyone who really has a feel for all the wildly different aspects of the city of Rome will understand what Respighi was 'getting at' when he wrote his 3 most famous pieces, the "Roman Trilogy" of symphonic poems. They are often judged disparagingly by critics (and even some musicians and audiences) as rather hollow 'picture-postcard music', with little substance under a (never disputed) veneer of brilliant orchestration. Not everyone knows that he was also responsible for delicate songs and string suites, mainstream concertos and much more restrained, almost 'neo-renaissance' works such as the 'Ancient Airs and Dances' Suites (although they probably would recognise the Prelude to 'The Birds' if they heard it!) When he wrote the Roman Trilogy his choice of exuberant style was quite deliberate, and I believe it reflects how completely in tune he was with the city, in all its variety and contradictions.

On these tours we will visit the places described in the 3 symphonic poems (as well as in one or two other relevant pieces),and some of the locations connected with his life. It isn't always possible to make a coherent 'itinerary' out of them - some work better than others; one of them also has "timings" specified in the programme-notes: you can even try to follow these if you want!

It may help to start with a short biography. Ottorino Respighi was born on the ninth of July 1879, not in Rome but Bologna. When his musical talent became obvious, he spent some time in Moscow studying under Rimsky-Korsakov, which no doubt helped to develop his natural talent for spectacular orchestration (some biographies also mention time with Max Bruch, but his wife Elsa refutes this). By 1913 he had returned to Italy: this was the time of his move to Rome, where he lived for the rest of his life. He was appointed to teach at the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia (between Via Vittoria and Via dei Greci on the Corso),which gave him the chance and the time to start composing in earnest; he was the academy's Director between 1922 and 1925. In 1919 he married Elsa (a former pupil).

The Fascist era was a difficult time for Italian composers (and artists generally); although Mussolini is known to have liked his music, and wanted him to declare support for the regime (as did certain contemporaries, who even dedicated works to Il Duce),Respighi, who was essentially apolitical, had to tread an uncomfortable path between relative acquiescence and risking outright alienation - a stance which has often been misinterpreted by some who read active support into it. He maintained a mutually beneficial relationship with the conductor Toscanini - significantly, a more outspoken critic of the Fascists - who made benchmark recordings of several of his pieces, including the Roman Trilogy. In his 50's he developed heart problems, and eventually died in Rome on 18April 1936, aged only 56. A memorial exists, as we shall see, in an unexpectedly familiar church, but after a few years his remains were re-interred in his home city of Bologna.

The three symphonic poems of the 'Roman Trilogy' received their premieres in the following years:

1916: Fontane di Roma

1924: Pini di Roma

1929: Feste Romane

These tours will deal with the three in chronological order.

1. FONTANE di ROMA

(Fountains of Rome)

Why did Respighi choose these particular four fountains, amongst the dozens across the city he could have picked? Part of the answer almost certainly is connected with the times of day he specified for each one: this element was just as important - it was the combination of the two that gave him the inspiration.

Here are Respighi's own programme notes for the piece:

"In this symphonic poem the composer has endeavoured to give expression to the sentiments and visions suggested to him by four of Rome's fountains contemplated at the hour in which their character is most in harmony with the surrounding landscape, or in which their beauty appears most impressive to the observer.

"The first part of the poem, inspired by the fountain of Valle Giulia, depicts a pastoral landscape: droves of cattle pass and disappear in the fresh damp mists of a Roman dawn. A sudden loud and insistent blast of horns above the whole orchestra introduces the second part,The Triton Fountain. It is like a joyous call, summoning troops of naiads and tritons, who come running up, pursuing each other and mingling in a frenzied dance between the jets of water.

"Next there appears a solemn theme borne on the undulations of the orchestra. It is the fountain of Trevi at mid-day. The solemn theme, passing from the woodwind to the brass instruments, assumes a triumphal character. Trumpets peal: across the radiant surface of the water there passes Neptune's chariot drawn by sea-horses, and followed by a train of sirens and tritons. The procession then vanishes while faint trumpet blasts resound in the distance. The fourth part,The Villa Medici Fountain, is announced by a sad theme which rises above a subdued warbling. It is the nostalgic hour of sunset. The air is full of the sound of tolling bells, birds twittering, leaves rustling. Then all dies peacefully into the silence of the night."

As well, then, as visiting the fountains themselves, you can, if you want, try to keep to his timings: you will probably get the most out of it if you do! It is actually possible to construct a sensible itinerary for the tour taking this into account - even if there may have to be a certain amount of delay between 'stops'. I have included in the notes some places you could visit in the meantime without taking you far out of your way.

If you are able to take an mp3 player along with you, you can even listen to the movements in situ!

Use the links in the box below to travel to each movement, and the places referred to in the course of the text.

1st Movement: The Fountain of the Valle Giulia at Daybreak

Villa Borghese

Galleria Borghese

Via Veneto

2nd Movement: The Triton Fountain in the Morning

Palazzo Barberini

3rd Movement: The Trevi Fountain at Mid-day

Accademia di San Luca

Piazza di Spagna

Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia

Towards Piazza del Popolo

4th Movement: The Fountain of the Villa Medici at Sunset

1st Movement:

The Fountain of the Valle Giulia at Daybreak

Rather unfortunately, we run into trouble straight away…! It is by no means clear exactly which fountain Respighi meant. The Valle Giulia is an area in the Villa Borghese Park, and the one road that actually bears the name ('Viale della Valle Giulia') has no fountain anywhere along it! Various local contenders therefore have to be considered. There is one at the western entrance to the park on Viale Washington - almost a nymphaeum , known as the Fontana di Esculapio.

It doesn't get my vote because of the less-than-peaceful stream of bus-traffic thundering past - if nothing else, the music of the movement surely depicts a more rural and peaceful setting.

The next contender is a wide round pond of green water with a strong, single fountain-jet in the middle. This has more claim, being definitely in the valley, and is also more rural (see the map to place it exactly); but it just seems a bit too open and public, and the fountain hardly 'trickles' in the way the music suggests.

2 other possibilities are the more formal fountains that face the Museum of Modern Art in Piazza Firdusi, or at the Etruscan Museum in the actual Villa Giulia; but again to me these are not rustic enough.

Even if I'm wrong, I have to say that the fountain that really seems to fit the music best is to be found a little to the east of the actual valley: it is at the junction of the Viale dei Cavalli Marini and the Viale del Museo Borghese, set back off the corner under some shady trees. It has a very attractive wide bowl to receive water gently trickling from the topmost dish, the smallest of a gradually widening set of marble basins. There is a convenient circle of stone seats around it. It is incredibly peaceful and evocative: I find it the perfect backdrop for the music.

To arrive here, it is a short walk through the park, a little way south from the Galleria itself. It used to be exactly on the route of the 116 bus, where it reached the furthest point on its journey through the Villa Borghese as it turned in a circle to return to its northern terminus just below the Porta Pinciana (see 'A Ride on Bus 116') - sadly this bus is no longer running, but others will take you close to the Galleria. If you can get there for a cool & balmy summer dawn, I think you will at least accept it as a good possible starting-point!

As far as the music itself goes, this is my favourite movement of the four. It evokes such a calm and languid setting - the first liquid string bars seem to emerge from nowhere, and as the birds begin to call, the fountain trickles gently away. There is some beautiful descending chromatic tinkling, especially at around 2 mins 20, and then again rising up at 2 mins 57; a magical pause before the main theme is heard again, answered by distant horns… the movement closes with the last word from the birds (aka oboe & clarinet!),but the early-morning peace is about to be shattered….

If you want to keep to the 'timings', strictly speaking you can head down to the next fountain when you like, as it is depicted only generally 'in the morning'. As fountains #2 & #3 are very close, however, and you are aiming to be at the third one at mid-day, you could spend a little time first exploring a little more of the park, especially the nearby 'Piazza di Siena' and the 'Temple of Aesculapius' with its little paddle-boating lake in front.

See below for some suggestions over how to plan out the morning! Best of all of course you could devote an hour or so to the wonderful Galleria Borghese only a hundred yards away - see 'A Ride on Bus 116' again for more details, and remember you need to book in advance. If all else fails, there is always the nearby zoo!

Depending which parts of the park you have explored, there are various ways of getting down to the next fountain. It is probably easiest to find your way back to the Porta Pinciana and then head down Via Veneto - plenty of coffee stops if desired by now! Otherwise, you could just catch Bus 52 or 53 from Via Pinciana just at the exit from the park beside the Galleria: it is only a few stops straight down to Piazza Barberini.

2nd Movement:

The Triton Fountain in the Morning

Arriving in Piazza Barberini in the heat of a summer morning is not always the most pleasant of options, as this is a particularly bleak and busy traffic hub (with the honourable exception of what we are about to look at!) In different circumstances it probably wouldn't be recommended; nevertheless, if the light is splashing off the water from Bernini's masterpiece and you are able to block out the roar of the traffic by listening to the second movement of the suite, it is an undeniably striking experience….

The fountain and the square have been described already in 'A Ride on Bus 116'; from the extra point of view of the music however, it is easy to associate the horn fanfares at the beginning of the movement with the water-god sounding his conch - and although over the last couple of decades the strength of the jet seems to have been reduced, the cascade of water depicted in the bars which follow is still very appropriate: listen especially to the climax announced by more fanfares at about 1 min 50. Apparently when the jet did fire higher, it achieved better Bernini's intention of filling the scallop-shell bowl upon which the Triton sits with its spray, which would in turn overflow into the basin below.

Whilst you are listening to this short movement, you can also appreciate the beauty of the overall design, with the four up-standing dolphins and the vigorous carving of the god; visible too are the bee-emblems of the Barberini Pope Urban VIII who had it built in 1642 to stand by his family Palazzo, within the inscribed coat-of-arms.

As remarked in the notes for the 116 Bus tour, the whole creation really deserves a far more congenial setting than this!

The next movement specifies 'mid-day' as the time of arrival. If you still have reasonable time in hand, you could always visit Urban's Palazzo Barberini, now an important gallery, at the corner of the Via Barberini heading from the side of the piazza.

This is another attractive museum, housing largely the Barberini family collection originally, but now taken over by the state as the 'Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica'. Many stellar names are represented amongst the artists: don't miss Raphael's 'La Fornarina' (supposedly his mistress),and Caravaggio's 'Narcissus' and the gruesome 'Judith & Holophernes'.

There are more intimate family possessions on view in the Barberini Apartments. Like the Galleria Borghese, the opulent settings of the rooms themselves are as impressive and inspiring as the works that hang there.

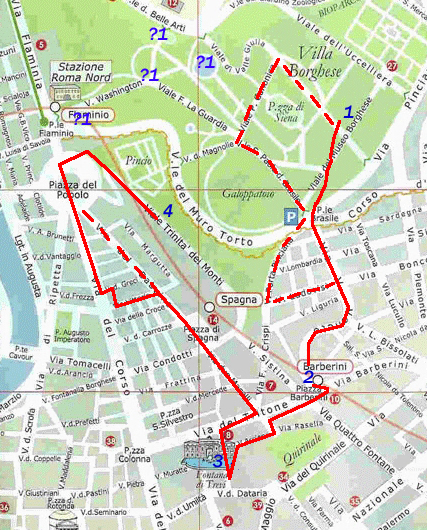

See the map above for the various routes you could now take to the next fountain - it is easiest really (if not very exciting) to resume the trail at the Triton Fountain, walk down the Via del Tritone until you get to Via della Stamperia on the left: take this road and you're there! - and click here for some suggestions again for what order to do things.

3rd Movement:

The Trevi Fountain at Mid-day

It is good to know that even before this - the most famous of all Rome's fountains - received its big boost of popularity during the Hollywood and Cinecitta years of the 50's, it was one of Respighi's choices for the suite. It is hard to block out from one's thoughts the iconic scenes in films such as '3 Coins in the Fountain' & 'Roman Holiday', not to mention Fellini's 'La Dolce Vita', with the likes of Audrey Hepburn and Anita Ekberg using its waters as a backdrop (or in Anita's case, for a rather more starring role…!); and without doubt, the effect that 50's chic had on the tourist-draw of the place will probably never wear off. It would almost certainly have grown its huge popular appeal anyway: I don't think anyone can fail to be moved by their first view, and not want to return or tell other people about it.

Many people assume that this is yet another masterpiece by Bernini; but in fact the palm goes to a much less famous, slightly later architect, Nicola Salvi (possibly following an idea by Pietro da Cortona). It was an inspired design actually to create the whole thing out of the back of a palazzo (windows from this building can be seen looking out almost through the jets of water),thereby making the best use of the cramped area available. One of the most striking things is how the fountain seems at the same time totally out of scale with the small piazza, but nevertheless wonderfully 'right'. Salvi took 30 years to finish it (between 1732 and 1762, under the auspices of Pope Clement XII) - it is said that the constant exposure to the mists of the water led to his death. The water itself comes from the famous Acqua Vergine conduit, still gushing forth from the purest spring in the city - it also feeds the Barcaccio at the Spanish Steps: a slightly more convenient place to have a taste…!

In the centre stands the majestic form of Oceanus himself, definitively 'ruling the waves'; the other figures in the tableau are all relevant in various ways: below Oceanus on either side are a pair of water-gods, holding the reins of his chariot - the horses are particularly vibrant and energetic.

The statues on the same level as him to left and right are supposed to represent goddess-personifications of "Health" and "Abundance"; on the next level above are scenes showing the legendary 'vergine' herself discovering the source of the 'acqua', and Augustus's right-hand man Agrippa overseeing the construction of the original aqueduct. Higher again are statues of the 4 Seasons, and a coat-of-arms of the Florentine Corsini family, of whom Clement was a member.

Respighi's music starts with a grand, slow build-up to portray the chariot approaching, and then settles into a steady rhythm, as it bounces along crashing amongst the waves - notice especially the big crest it smashes into at about 48 seconds into the movement! - accompanied by fanfare conch-calls from the Tritons. An even bigger wave is negotiated at around 1 min 5; and then the tempo increases a little as the chariot skims along unhindered, until the drums return for the crescendo of the biggest breaker of all at 1 min 27. From there, the chariot gradually recedes further and further into the distance, still with fanfares blaring. Without doubt Respighi must have thought Salvi had done a good job!

The marble seats were added later, when people realised how popular the attraction was; the custom of throwing a coin over your shoulder in order to ensure your return to Rome seems only to have developed at the end of the nineteenth century (the coins are periodically collected and distributed to charities) - but if you ignore it, I guarantee you won't ever stop wondering whether you've made a big mistake…

If you haven't had a coffee already (or even if you fancy another one) there is a typically Roman bar (Bar Fontana di Trevi) - the first bar I ever visited in Rome, and still a regular place of pilgrimage - at the lower right-hand corner of the fountain. You can stand at the door and just gaze at the (second-)most famous view in Rome.

To some extent, as you head away from the fountain, you appreciate the effect Respighi achieved at the end of the movement: gradually the splash of the cascading water and the buzz of the crowd grow less and eventually fade completely - you can imagine Respighi reluctantly dragging himself away.

Now there is, timings-wise, a good few hours to fill before you need to arrive at the final fountain. The first priority, of course, is lunch! I am a little out of my usual haunts around here to make firm recommendations, but 'Al Piccolo Arancio' in Vicolo di Scanderbeg certainly used to be a good bet (try their unusual orange-flavoured pasta!). This is only a couple of streets away; from then on, see the map for a suggested route to continue on the tour from there - or at least back and on again from the fountain itself.

Whether or not you are actually following the 'time-of-day' itinerary, there is a helpful bus-route that will take you near enough to the Villa Medici. Starting from the Trevi Fountain, walk around to its right side and leave by the road heading away behind it (Via della Stamperia). This takes you into the small piazza of the Accademia di S Luca, which (hopefully still) houses a small museum.

Truth to tell, this is one of the more 'missable' galleries in the city, but if you have already explored Palazzo Barberini earlier in the day it can use up a bit of time - assuming it has actually re-opened: it has (until recently?) been closed for some years. It does contain a few pieces worth the visit, including works by Canaletto and Titian, a collection of cat-studies by Rosa and (probably the highlights) a sweet little putto by Raphael ( a fragment of a fresco) and a lovely Venus by Guercino. The gallery evolved from donations and bequests from artists who had attended the Academy to study (art, naturally enough!) It was originally founded in the sixteenth century, but was only moved here when Mussolini destroyed its old home (along with those of many other blameless citizens) in the old quarter of the city which was demolished to make way for the Via dei Fori Imperiali.

From the piazza, cross the main road, Via del Tritone, and then walk a short distance uphill until you reach Via dei Due Macelli leading off to the left: turn down this road. Not far along on the side opposite is a bus-stop. Here you can either catch a 119 more-or-less to the 'door' of the Villa Medici; or carry on by foot to Piazza di Spagna and climb the Spanish Steps. However, in this district we are also very close to another couple of places very relevant to Respighi in Rome - two more good ways of spending an hour or two while you wait for the late-afternoon/sunset specified for your final destination.

If you choose to walk to these (you could, before September of 2014, have travelled by bus, but the city bus-company has sadly removed this option!) simply carry on (past the Column of the Immaculate Conception in Piazza Mignanelli) until you reach the Spanish Steps (for more information on this wonderful district see 'Talking Statues' and 'The Obelisk Trail'). To get straight to the Villa Medici, you could climb them now; but I really recommend that you go a little further out of the way to see the other two relevant places. Carry on then to the far side of the square and walk a short way along Via del Babuino; then turn left down Via Vittoria. A little before the street meets the Corso (past a very useful little supermarket!) you will come to the entrance of the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia.

It was here that Respighi held a teaching post from 1913 (the reason for his move to Rome) and then was Director for three years between 1922 and 1925. It remains a very prestigious and highly popular college for young musicians - the second concert of the 2011 Proms season in London featured singers and musicians from the Conservatory performing Rossini's opera William Tell (and not just the overture!)

You may get away with walking through its main corridor, alongside the attractive (but glassed-off) garden to the 'back entrance' on Via dei Greci - I occasionally dare to do so, partly as a sort of Respighi-pilgrimage, and partly because it brings me out opposite the hotel where I invariably stay in the city, the Hotel Mozart; one of its most pleasant attractions is the sound of the students practising across the street from my hotel window!

If you do get through without being challenged (you could always try invoking the name of its former Director…),or even if you carry on to the Corso instead and walk up alongside, when you get to Via dei Greci cast your eye up its length to the characteristic arch over the road at the far end. This is one of the prettiest of the pedestrian alleys at this top end of the Corso. As well as the Hotel Mozart and its sister bistro-ristorante 'La Luna d'Oro' it also contains a music bookshop - one of the handful of bookstores in Rome which stocks books in English.

To return straight away to the Spanish Steps, walk up to the far end of Via dei Greci. On the left corner you can pay your respects to the wonderfully grotesque 'Baboon' fountain (see 'Talking Statues') and then turn right. Almost opposite the Baboon is a very useful bus-stop for the 119 running down to the city-centre at Piazza Venezia - another good reason for staying at the Mozart!); it actually travels first via Piazza del Popolo, where we shall be continuing the tour; or you could walk the 3-minute-or-so distance up the Corso from the other end of Via dei Greci to the Piazza, as described below.

This takes you first (on the left) past the church of S Giacomo degli Incurabili - long associated with the hospital beside it (it also goes by the name of '…in Augusta', as a couple of streets back stands the family Mausoleum of the first of the Emperors, at last partly restored and open for visits); on the opposite side is the unexpectedly spacious and ornate church of Gesu e Maria, designed in the 1670's by Rainaldi.

Just a little further on is the 'House of Goethe', a small museum of memorabilia to mark the building where the poet lodged for a couple of years in the 1780's. As well as the exhibits, there is a small library which students can use.

Alternatively, you could walk up to the Piazza by turning left from the Baboon. This way you will pass first on the left the Greek Orthodox church of S Atanasio, whose characteristic twin dome-like bell-towers are a readily-identifiable landmark along the northern skyline of the city; almost immediately after it is All Saints, the Anglican church in Rome - with an even more conspicuous white-tipped tall and slender campanile.

Running parallel on the right is the Via Margutta, traditionally a bohemian artists' quarter: there are some unusual galleries and working studios still in residence today - not to mention a suitably 'bohemian' eatery in the form of Rome's top vegetarian restaurant, Osteria Margutta.

The final point of interest (if you can tear your eyes away from the amazing window displays, as the jaw-droppingly pricey antique shops and designer clothes stores vie for your attention) is at the end of the road on the right, in the form of the classy (with price-tags to match the area) Hotel de Russie - still a favourite, as it has always been, of the rich and famous…

By whichever route you have arrived, before you now stretches out the Piazza del Popolo, fully described in 'The Obelisk Trail'. Mentioned there too is the church at the far side, beside the city's north gate: S Maria del Popolo - the story of whose origin on the supposed site of Nero's tomb need not be repeated here. It is time, though, to explore it in a little more detail inside.

Even before D. Brown Esq. succeeded in attracting even more visitors to this treasure-house, it was a real must-see for art lovers, with a roll-call of contributors to match any church in the city. There is far more to it than just the Chigi Chapel (which is what draws the majority these days, first on the left),with its designs by Raphael (including the pyramid) as well as finishing touches by Bernini - his pointing angel, for some time rather petulantly concealed behind a tarpaulin, as if deliberately to frustrate the Angels & Demons brigade, is now once again on display.

The other highlights include frescoes by Pinturicchio (especially in the vault behind the altar and the third chapel on the right); fine marble-work by Fontana (second chapel); designs in the apse by Bramante, with some of his earliest plans for St Peter's; two lovely tombs by Sansovino….the list goes on and on, even before you reach the masterpieces in the Cerasi Chapel (far left). Here is a picture of the Virgin by Caracci, no mean artist; but even he is eclipsed totally by two of Caravaggio's finest: the Crucifixion of St Peter, and the Conversion of St Paul. Somehow, 'encouraging' the Dan Brown fans to look further doesn't seem such a jealous aim after all…

But how does all this fit into the tour? Make your way to the far right transept and look for the doorway out to a corridor leading to the sacristry. Amongst the memorials along the wall, you will find one to Respighi. It is not mentioned, as far as I know, in any of the regular guide-books, which makes it all the more satisfying to discover. This monument was the earliest raised to him before his remains were returned to Bologna - a befittingly local memorial for a great 'artist' from the musical world amongst those masters of the visual variety.

If you are still keen to keep to the timings, you may yet have an hour or so on your hands. It is pleasant just to sit in the Piazza for a while under the Obelisk amongst Valadier's lions - and you could always have some refreshment at either of the two famous cafés Rosati or Canova on either side of the square (see 'The Obelisk Trail').

To reach the final fountain you will eventually need to take the (steepish) steps at the back of the church up to the Pincio Hill, where you can admire the view over the Piazza across to St Peter's from the terrace of Piazzale Napoleone; and maybe have a wander through the Pincio gardens ('Obelisk Trail' once more).

It is then only a short walk downhill from here to the Villa Medici: if you don't mind foregoing a guided tour actually in English (they take place once a day at 12.45),you could still join in on one and spend an hour exploring the gardens.

4th Movement:

The Villa Medici Fountain at Sunset

You don't need at all, in fact, to pay for entrance to see your final target: the fountain itself is not to be found within the Villa's grounds - which are unusually fountain-free as far as these grand family piles go. There is a small one incorporated below the statue of Mercury by Giambologna just below the back façade of the villa; although this is the spot where the statue was commissioned to stand, the one there today is a copy: the original is in the Bargello in Florence - and it has been endlessly copied ever since (including for the middle of Christ Church's Tom Quad in Oxford!)

Another 'fountain' of sorts seeps up from the ground amongst a tableau depicting the killing of Niobe's children (again, a modern copy: the originals are also in Florence).

But the famous one we are here to see stands in front of the Villa's main entrance, across the road next to the balustrade looking over the rooftops below.

It is quite a simple design (by Annibale Lippi, in 1589),but hugely effective: a gentle jet of water shoots, only a couple of inches high, from a bronze cannon-ball in the middle of a wide and shallow red-granite dish of Ancient Roman origin (sadly it is not always working). The story attached to it is that the cannon-ball was fired, rather randomly, towards the Villa from Castel Sant'Angelo by the eccentric Queen Christina of Sweden who was by then living in the city. Apparently it was her way of sending a message to one of the artists-in-residence at the Villa that she would be late for their arranged meeting…rather more romantic than just texting him, I suppose…

Respighi's music for this movement recreates very authentically the magical golden calm that settles over the city (particularly here on the edge of the Pincio) when the sun starts to set, and the bells of the district's churches begin to peal, almost like water gently dripping. To sit on the hillside, or to stand overlooking the rooftops in all shades of burnt-ochre and orange as the peace of evening slowly settles around you is an unforgettable experience.

The nostalgic main theme of the movement evokes this atmosphere perfectly: you can almost hear the gentle rustle of the ilex branches (listen at around 50 seconds onwards); he is a master too at imitating the calls of birds - there is a lovely example at 1 min 53 onwards, and especially from 2 mins 15. The sound of the bell languidly pealing is another masterstroke: it isn't really 'in tune' with the tonality of the rest of the music, but sounds exactly right nonetheless. The last minute or so of the piece is just matchless: everything has imperceptibly died away, the birds have ceased singing - only the last solitary bell is left as the music disappears into the enveloping dusk.

"The Fountains of Rome" was an immediate success (rather more so than the two to come…!) and surely not only gave Respighi the encouragement he needed to continue his Roman 'theme', but also raised his standing amongst the modern composers of the early twentieth century to that of an undisputed master. Even greater things were to come!

2. PINI di ROMA

(Pines of Rome)

After his success with the "Fountains", Respighi (now Director of the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia) started work on what was to become the middle piece, and eventually the most famous, of his Trilogy.

Other cities of course have pine trees… but it was a stroke of genius to realise how iconic and essential the Roman ones are to the whole atmosphere of the city. Even people who have never heard the music of the piece itself understand and have embraced the picture of Rome that its title immediately conjures.

Respighi's own programme notes read as follows:

1. The Pines of the Villa Borghese

Children are playing in the pine groves of the Villa Borghese. They dance in circles and march to mimic soldiers and battles. They are excited by their own cries, and, like swallows at evening, they disappear in a swarm. Suddenly the scene changes and….

2. Pines near a Catacomb

…we see the shadows of pines crowning the entrance to a catacomb. The sound of mournful psalm-singing rises from the depths, floating solemnly on the air, gradually and mysteriously dissipating.

3. The Pines of the Janiculum

In the trembling air, the pines of Janiculum Hill stand, outlined distinctly in the light of a full moon. A nightingale sings.

4. The Pines of the Appian Way

Misty dawn on the Appian Way. Solitary pines guard the tragic country. Indistinctly, incessantly, the rhythm of innumerable steps is heard. The poet imagines a vision of ancient glory; at the sound of trumpets in the brilliance of the sunrise, a consular army bursts forth towards the Sacred Way, marching in triumph to the Capitol.

Unlike the 'Fountains', Respighi does not try to create a set of times of day to link the pieces in a continuous itinerary; only the last two movements refer specifically to the hours they are meant to portray, and so it is pointless this time to try to construct a cohesive 'tour' around the movements in chronological order - I am not going to recommend that you spend the night on the Janiculum and then try to get to the Appian Way for daybreak!

What I can do is suggest ways and means of getting to the settings involved, and then describe them, with once again comments on how they are depicted in the music.

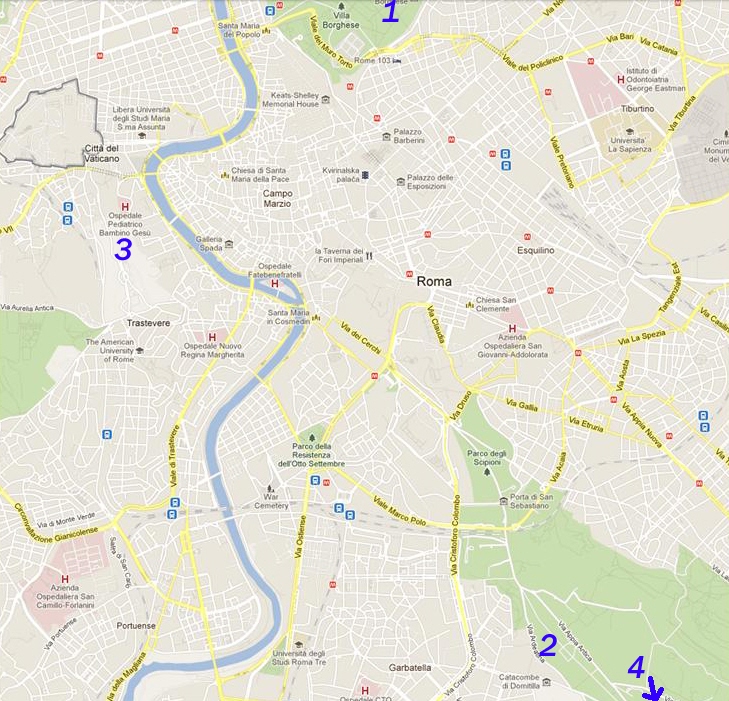

The location map below gives you an idea of how far-flung they are this time compared with the 'Fountains'.

As ever, click on the links in the box below to move quickly to the different movements and some of the places of interest described with them.

1st Movement: The Pines of the Villa Borghese

Pincio Hill

Villa Borghese Park

2nd Movement: Pines near a Catacomb

Catacombs of S Sebastiano

Catacombs of S Callisto

Fosse Ardeatine

3rd Movement: The Pines of the Janiculum

Bramante's Tempietto

The Janiculum Hill

4th Movement: The Pines of the Appian Way

Domine Quo Vadis

Parco degli Acquedotti

Via Appia Antica

1st Movement: The Pines of the Villa Borghese

If you have already 'done' the Fountains tour, or indeed followed any of several others on this site, you will have spent time already in the Villa Borghese park; and I apologise if some of the notes following repeat themselves rather! It is the most easily accessible and popular of the city's public gardens: locals as much as (perhaps even more than) visitors love to head there at weekends or 'festivi'. Whatever the time of year, you will practically always find happy family groups, or bands of youngsters or students, trying out the various bikes and pedallo-carriages you can hire, walking their dogs, or just relaxing under the shade of the pines themselves. An increasingly popular new addition to the 'bikes for hire' collection is the wonderful-looking (no, I haven't tried it…yet!) 'Segway' - a powered little moving platform that you can just stand on and zoom around the park holding onto a simple upright handle to steer with! Even more popular nowadays of course are the ubiquitous e-scooters... also added to my list! The usual place to hire any of these (if you so wish) is at the end of Viale delle Magnolie, where it adjoins the Pincio gardens.

There is also a little café there, and it is not far from a small theatre which gives various regular shows; there is sometimes a puppet theatre there too (see the third Movement - Roman kids love their puppets!)

The Pincio gardens extend via various criss-cross walkways, lined with busts of famous Italians on pillars, to an open square with Hadrian's obelisk memorial to his beloved Antinous, who drowned in the Nile saving the Emperor's life (see 'The Obelisk Trail').

The parks were in ancient times owned by the vastly wealthy ex-general, politician, Epicurean philosopher and gourmet Lucullus, who is renowned (amongst other things…) for introducing the first cherries to the Roman world. I think he'd probably have approved of the pleasure his old gardens still give to his descendants!

Also in the gardens you can find an unusual fountain (recently repaired) in the form of a water-clock.

Further from here the gardens stretch back to the Piazzale Napoleone I, still one of the most romantic places for lovers' trysts in the city: its views over the Piazza del Popolo across the north of the city to the Vatican are amazing, especially at sunset.

Walking inwards from the bike-hire end of Viale delle Magnolie, you cross over the unlovely main road which is here known as the Viale del Muro Torto (thankfully well hidden from view); then you pass (down the hill on your left) a large circular pond with a fountain, and on your right the area called the Galoppatoio - used more by joggers than riders! It is a shame that the tethered scenic-view balloon has been taken away - its old 'launching-pad' can still be seen: it used to give unbelievable views over the city.

One of the underground walkways from the Spagna Metro station also emerges close to here on the far side of the big open field.

At the other end of the road you stand opposite the entrance to the central and original part of the Villa's gardens at the small roundabout in Piazzale delle Canestre.

Walking up the Pincio Hill is one way to get here; another of course is to come by bus. Sadly the little electric 116 is no longer running: it used to turn into the park at this point, having arrived via Via Veneto and the Porta Pinciana - for a whistle-stop tour past many of the park's main attractions this was an excellent bet (see 'A Ride on Bus 116'),and we can only hope it will be reinstated one day. For now, several buses run to the top of Via Veneto, from where it is not an arduous walk beneath the Porta Pinciana to reach the Piazzale; at the little roundabout, head right.

Through the gateway there is a welcome snack kiosk on the left - or for free a drinking-fountain on the right. As you walk through the park from here, the peaceful atmosphere of the lovely green open areas is a world away from the bustle of the city, and the Pines themselves contribute hugely to this sense of space. After a short walk, paths lead off to the left and right: head once again to the right. You will pass the so-called Casina di Raffaello, and then come to the little reproduction 'Temple of Diana'; carrying on and turning left takes you past a monument to Umberto I up to one of the city's most delightful fountains - the Fontano dei Cavalli Marini, where the "sea-horses" seem about to leap straight out from the water to have a canter around the park.

If you have looked at the 'Fountains of Rome' tour you will know that set back under the trees over the road from here is my identification (and I'm sticking to it!) of the first fountain depicted in Respighi's earlier tone poem.

A little further on brings you to the wonderful Galleria Borghese (see 'A Ride on Bus 116' for this and other notes about the park's evolution).

Turning left from the sea-horses you travel along the length of the circus-like 'Piazza di Siena', which hosts equestrian events and sometimes summer concert performances.

At the decorative arch of the 'Temple of Faustina' on your right, turn left again, past Rome's own 'Globe Theatre'.

Then head back towards the Piazzale delle Canestre - but before you reach it, take the path opposite where you originally turned (now on the right!) which will bring you through the Giardino del Lago to the little boating-lake itself, watched over by the 'Temple of Aesculapius' (not original, despite being the Park's usual 'poster-boy') and surrounded by orange-trees.

The whole park, in fact, is quite delightful: there is plenty more to it that you can explore yourself, including a zoo (sorry, 'bioparc'). The electric scooters etc are of course a bit modern for Respighi's time, but his music still creates an authentic atmosphere of the liveliness and fun you would be likely to find there on a fine weekend.

Its opening bars immediately sweep you into a happy, noisy setting, with families laughing and chattering while the kids chase each other around: you can imagine them charging in and out of the pines and hiding behind them (around 40 seconds onwards!) There seems to be some sort of friendly argument going on between 1 min 5 and 1 min 22…definitely some name-calling involved… Fanfares suggest a game of soldiers: the cheerful march Respighi himself describes in the programme-notes comes in at 1 min 50. On go the games until the first of a repeated blast of trumpet-calls at 2 min 20 (so discordant to early twentieth-century ears that they led to boos from the audience at the first performance) which bring the movement to an abrupt end - papa breaking the mood by shouting 'Time to go home'?

In this first movement Respighi sets the tone for the whole piece, and we realise that unlike the 'Fountains', where the subjects themselves coupled with that particular time of day were the focus, this time it is the scenes upon which the ubiquitous Pines look down that are the real inspiration for the music - not the trees themselves. This is never more true than in the movement next to come.

2nd Movement: Pines near a Catacomb

Most of us have our own ready-formed idea of what catacombs represent, and the function they had in Ancient Rome; this may not necessarily however, as history is beginning to reveal, be a correct one. They are not now thought actually to have been Christian hiding-places to escape the periodic persecution under some of the less tolerant emperors (Nero, Decius, Valerian and Diocletian were some of the most severe). They seem rather to have served simply as burial places, and in some cases chapels or meeting-places.

How was this allowed to come about? The usual method of dealing with the dead under Roman religious custom was cremation - on top of which, it was illegal to build tombs inside the city-walls (there was an extensive cemetery outside the Esquiline Gate, where urns of ashes were interred). To the Christian mind however, expecting the imminent return of the Messiah to raise the dead, such a drastic and irreversible practice of destroying the body was abhorrent. We know that it was common practice to form 'burial clubs' to pay for the digging or building of tombs - it was reasonably easy even for Christians (many of whom, remember, were Roman citizens themselves) to band together to finance these, with few questions asked about what form they would actually take.

Over the centuries then, these burial complexes grew and grew: the soft tufa rock was relatively easy to cut through, especially to the south of the city where the biggest examples exist - far easier, in fact, than trying to construct above ground the increasingly large numbers of burial chambers that were needed: and an actual body of course takes up far more room than just an urn of ashes. The biggest source of available space was thus underground. The largest (e.g. those of S Callisto) sank five levels down eventually and held thousands of niches ('loculi') for the bodies to lie in.

It is also easier to understand why they remained intact, even under the years of serious persecution, when one bears in mind that the Romans had in general great respect for the dead: they were not likely to go in and destroy these sacred areas, even when constructed by a non-mainstream cult such as Christianity.

The name 'catacomb' is believed to have originated at the particular site beneath the Patriarchal Basilica of S Sebastiano on the Appian Way. S Sebastiano itself will be described in a future tour; relevant to mention now though is its original dedication as a pilgrimage church to Sts Peter and Paul, whose remains were temporarily moved from their own basilicas of S Pietro and S Paolo fuori le Mura during the savage persecutions under Valerian (Sebastian became the dedicatee only later - he was executed under Diocletian). This made them, of course, exceptionally holy - not to mention 'desirable' in estate agent terms…! For this reason too, they were the only chambers never to have been 'lost' since ancient times.

If you visit these, you will be shown an extraordinary 'open' area - even though it is still underground - with four or five almost free-standing tombs (somewhat resembling a small row of beach-huts!) which are thought to be amongst the oldest examples; they were described as being situated (in Greek) 'kata kumbas', meaning 'beside/near the hollows' - the excavation having originally been a stone-quarry, by then abandoned. The epithet came to be used for the burial complexes generally.

As time passed, and the first fathers of the faith became more firmly established, even Popes themselves were laid to rest in the Catacombs, as were some of the early martyrs. At the catacombs of S Callisto (which, along with those nearby of S Domitilla, I would most suggest visiting for the purpose of this 'tour'),for example, exists the first burial place of St Cecilia, whose body was only later moved to what became her own church, built over her family's house in Trastevere.

More sacred still is the Papal Crypt, which contains the tombs of no less than nine Popes of the third century, mostly martyred under Valerian.

The whole S Callisto complex, looted by barbarians and fouled by malaria, was lost to history until its rediscovery in the early 1600's, and then fully explored by de Rossi in the 1850's. It is said that when de Rossi announced to Pope Pius IX that he had found the tombs of so many of his predecessors, Pius accused him of having simply dreamed it. Dissolving into tears when being shown inscriptions from the crypt as proof for himself, Pius exclaimed 'Do I really hold in my hand the tombs of my ancestors?'; to which de Rossi retorted: 'But then, it's only a dream, Holy Father!'

To get to these sites, the most convenient way is to start in front of the Basilica of S Giovanni in Laterano, where there is a bus-stop for Bus number 218 (they run every half-hour). This bus takes you, along the outside of the city-walls, to Porta S Sebastiano; then a short way along the Via Appia to the church of Domine Quo Vadis (see the fourth movement),before branching right along the Via Ardeatina. Two stops on, you should get off: you are on the Via delle Sette Chiese. Walk back a short way, where you will see (on your right) one of the entrances to the S Callisto Catacombs; and a little further along on your left is the main entrance for those of S Domitilla. Both complexes offer regular guided tours in English. The equivalent bus-stop in the opposite direction will take you back to S Giovanni, where there is a Metro Line A station, and plenty of buses to the city centre (including the little electric 117 to the Colosseum and Piazza di Spagna.

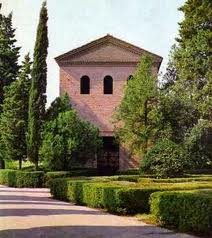

'Christ and Apostles' Fresco - S Domitilla

Incidently, and even more poignant perhaps for having occurred after Respighi's death, this bus-stop is only a hundred yards or so from the monument to the 335 innocent Italians executed by the Nazis at the Fosse Ardeatine themselves, in reprisal for a resistance-led bomb blast in the city which killed 33 German soldiers during the Second World War - more martyrs in their own right for the Pines to stand sentinel over.

I have picked these particular catacombs as those I suggest you visit mainly because they are in a more open area, and also because you can combine the visit with an exploration of the Appian Way for the fourth movement; there are others around Rome, in particular S Priscilla, but the modern incarnation of the Via Salaria around those creates too urbanised a setting. Others, a little more attractive, you may consider visiting are those beside the church of Sant'Agnese on Via Nomentana. It is a little ironic that the most common tree around S Callisto is the cypress… (it's OK, there are plenty of pines too!) Nevertheless, to return to Respighi's intention, it hardly matters which particular catacombs you visit: the important thing is the mood evoked from the general picture of the subterranean Christian gatherings which the trees witnessed in the early centuries of the faith.

The movement starts with some low and almost eerie chords, as if the Pines are looking quietly into the hollows of the ground - a deliberate and very effective contrast with the bright bustle of the previous movement. As the higher instruments begin to join in (1 min 35),it is almost as though we are being drawn into the assembly itself - a solemn ritual, perhaps an actual burial. Then, magically in the distance, a solo trumpet begins to play (2 mins 5) - designated physically 'lontana' in Respighi's score, and often placed apart from the main orchestra in performances, sometimes even at the back of the hall. Its music will be taken up by fuller forces at the movement's climax, but first here it seems to sound an early voice of hope - the actual depiction of 'belief' itself perhaps in a happier existence both for the soul of the dead man and those left behind to mourn and wait.

A rhythmic plainchant begins, interspersed with fragments from the trumpet's theme now on the lower wind instruments. The chant grows more passionate, until the lone trumpet's music bursts forth again above it on the trombones (4 mins 5) as the two themes merge into a paean of religious fervour. It gradually subsides, and our vision of the caves 'pans away', leaving only the Pine-trees to observe the ancient scene once again.

3rd Movement: The Pines of the Janiculum

The Janiculum Hill ('Gianicolo' to the Romans today) took its name from the ancient god Janus, who traditionally had a shrine built there. It stretches in a long north-south ridge parallel to the Tiber on its far bank, a little below the Vatican on the map. It was never one of the canonical 'seven hills' (mind you, the seven that actually were counted as such changed and evolved as the city gradually expanded),and was only enclosed by a city wall in the time of Pope Urban VIII. Before that, it had begun to be fortified in the last years of the Republic, and had partly been contained in the Aurelian walls. The legendary king Ancus Martius (fourth of the seven) is said to have built the Sublician Bridge ('Pons Sublicius') over the river to connect it to the city (one of his predecessors, King Numa, had been buried there) - only for it to be destroyed again by Horatius, as he kept the attacking Etruscan army at bay when the last of the kings, Tarquinius Superbus, was trying to regain his throne with the help of his erstwhile enemies under Lars Porsenna.

In much more recent times, it saw even fiercer fighting: it was the site of the Risorgimento Roman Republic's last stand under Garibaldi in 1849, as the French army trying to re-instate the Pope to his traditional throne made wave after wave of assaults upon the Porta S Pancrazio at its southernmost end. Statues were raised in commemoration, as we shall see, and a single cannon-shot is fired there every day at noon as a further mark of respect for the fallen - it can be heard all across the city.

Respighi's impression of it is far less martial - he depicts it in the stillness of a moonlit night. There are large groves of pine-trees covering the hill - and even more on its western slopes, which border Rome's largest public park, the Villa Doria-Pamphilj. Avenues of pines (and, plane-trees) also line the 'Passeggiata', a road running the length of its crest, along which another useful bus (the 115) travels in a circular route down to Trastevere and back, with convenient stops near some interesting monuments, fountains and churches.

To actually reach the hill, you have various options, depending really upon where you start from. If travelling from the city-centre, by far the easiest way is to catch the 115 mentioned above, or another bus, the 870: both these leave from a capolinea at Via Paola just off the Corso V Emanuele II near the river, and take you to the top of the hill.

A more interesting and attractive way of approaching from a different direction is to start from Trastevere (to get there, take a #8 tram from Piazza Venezia). Head for S Maria in Trastevere, and then leave its Piazza by the road at the far right (Via della Paglia).

Continue along this road until you reach Vicolo della Frusta on the right; at the end of this alleyway you will see a staircase leading up, onto Via Garibaldi. Turn left at the top: a short way along opposite is another staircase (it has a gate in front, but you will be unlucky to find this closed),which cuts off a hairpin on Via Garibaldi. This way not only gives you a pleasant view over Rome's Botanical Gardens to your right, but brings you almost at once to one of the jewels in the city's crown, set in the courtyard of the church of S Pietro in Montorio.

The Janiculum was known in antiquity as 'Mons Aureus' (Golden Hill) from the yellow-coloured sand that can still be seen to cover it. This church perpetuates the epithet in the Italian version of the name. In itself, it is not all that interesting - its main treasure is probably a fresco of 'The Flagellation' by Sebastiano del Piombo; but in the courtyard stands one of the loveliest buildings of the early Renaissance, if not of any period, in Bramante's Tempietto.

This tiny shrine is very simple and graceful, with 16 Doric columns supporting a well-proportioned dome. Bramante designed it at the very start of the sixteenth century, to mark the exact spot at that time believed to have been where St Peter was martyred. We know now that the description of his upside-down crucifixion "between 2 metae" really referred to the two ends of Caligula's Vatican Circus: but then the meaning was interpreted as being at the mid-point between two widely-apart structures in the city, traditionally called the 'Meta of Romulus' and the 'Meta of Remus'. Astonishingly, the latter still exists: it is better known as the Pyramid of Gaius Cestius in Piazzale Ostiense beside the Porta San Paolo!

The other, you may be even more surprised to hear, was another pyramid, which stood somewhere between the Vatican and Castel Sant'Angelo; it was demolished at about the same time that the Tempietto was built. Pyramids possess only a vague resemblance to the conical metae of the circuses, but these beliefs spring up in the unlikeliest fashion! Obviously Dan Brown wasn't the first person to start drawing lines across a map of Rome….

It is possible to arrange entry to the Tempietto if you are determined enough, but there is nothing in particular inside that is really worth the trouble: the building itself is the real work of art. As a template for the designs in the years to come it was never rivalled; St Peter's, for example, in comparison seems very bulky and clumsy.

From here, continue uphill past a monument to Garibaldi's band of defenders to the large Fontana del'Acqua Paola, built in 1612 for Pope Paul V by Giovanni Fontana, and completed with the large granite basin by his son Carlo. It is 'powered' by the waters of the Aqueduct of Trajan, running all the way from Lake Bracciano nearly 50 km northwest of the city. Four of its pillars came from the original St Peter's.

If you are on foot, you can enter the Passeggiata on the right at this point; the buses continue a little further to a roundabout which stands at the site of the Porta S Pancrazio, largely destroyed by the French assaults in 1849.

Both the road and the path now travel along the top of the ridge through avenues of pines, and gradually open out onto fabulous viewpoints down over the city, where you can try to pick out large numbers of familiar monuments and churches: try and spot the Pantheon!

The central wide piazza has a monumental statue of Garibaldi himself.

In the open space beside, there is a little refreshment kiosk, and here too is the home of probably the most famous puppet-theatre in the city, giving regular shows in the summer to the delight of the younger visitors. Until quite recently it was performed by a great old stager who had been operating Pulcinello & co for something like 50 years.

Below the terrace here is where they keep the cannon, wheeled out daily as mentioned above.

Further on along the ridge, now sloping downhill, you reach another statue, this time of Garibaldi's Brazilian wife Anita; it's a wonderfully swashbuckling affair, portraying her astride a rearing horse, holding a pistol in one hand and a baby in the other…. I suspect the French soldiers might have been more scared of meeting up with her than with her husband!

On the slope of the ridge above the Botanical Gardens is a little tower (in fact a light-house, flashing in the red, white & green of the national flag); standing nearby is "Tasso's Oak", beneath which the great poet is supposed to have liked to recline, presumably awaiting inspiration.

The Passeggiata ends in a zig-zag bend beside the church of Sant'Onofrio, next to a Monastery which is currently home to an order of American monks.

All along the ridge you have views down also over the opposite side of the valley, towards the park of the Villa Doria-Pamphilj. There are pine-trees everywhere, and it is easy to imagine this as the spot for Respighi's vision of the still night-time scene lit by the moon.

Finding anything specific that the music actually represents is probably a pointless exercise in this movement. After the silver shiver announced by the piano at the beginning, the atmosphere is beautifully evoked by a solo clarinet delivering a series of (horribly exposed!) wistful tunes over some vibrant long string chords. Is it meant to be a bird? Possibly; but probably the most famous passage in this movement (if not the whole piece) is the last section, where Respighi called for an actual recording of a nightingale over the last shimmering string chords, declaring that no normal instrument could produce the effect he wanted. Famously, of course, he thereby earned the piece its second set of boos from the audience at its premiere; the use of such new-fangled mechanical equipment in a "classical" piece was too much for them. It is odd to think that this is still something of a talking-point even these days: I suppose it still doesn't quite square with what we expect from a piece of orchestral music. However, in modern performances, it is far easier to 'cue' the recording at a suitable volume-balance than it was then, using a 78 gramophone record, and we can more fully appreciate the effect the composer intended.

If this aspect of the music has received the most criticism, the rest of the movement, even then, earned Respighi some of his greatest praise. There are some beautiful phrases on individual instruments (never mind the virtuoso clarinet),for example the oboe tune at 3 mins 6, answered by a solo 'cello at 3 mins 28; the two occasions where undivided strings come to the fore-front (a soaring statement of the clarinet's theme by the 'cellos in unison at 1 min 58, and the violins in full voice echoing the oboe at 3 mins 42) are majestic; and there are lovely effects of chromaticism, impossible to deconstruct and 'explain', especially at 2 mins 15 and from 4 mins 17 onwards. These really seem to depict in a particularly vivid way the gentle rustling and swaying of the trees in the breeze, and the peaceful aspect of the hill in the silver moonlight.

As the movement draws to the end with a repeat of the piano's opening arpeggio and one last reprise of the first theme from the solo clarinet (now more exposed than ever!),the chirping of the recorded live nightingale over the shimmering string chords, if sensitively timed and balanced, can leave a magical and moving impression of the poet's vision.

4th Movement: The Pines of the Appian Way

To describe all the monuments along the length of the Appian Way would take up far too much space, and they can be found fully covered in the better mainstream guide-books. I will mention here a few of the areas you may want to visit, with some particular points of interest; but once again, it is important to remember that Respighi's intention was not to depict the physical reality of the road itself, but rather what it stood for, and the scenes of glory and triumph it had witnessed in ancient times.

The actual music speaks for itself here - if there had been a couple of passages in the earlier movements which the first audiences found hard to swallow, at least the finale brought them to their feet, unreservedly applauding and cheering with approval for this masterpiece of crescendo and aural spectacle.

To reach the Appian Way is relatively straight-forward: the 118 bus from Piazzale Ostiense, with stops at the Circus Maximus and the Baths of Caracalla will take you to the second milestone or so; after that, however, the best of the monuments and the most characteristic stretches of the road really have to be done on foot, as for most of its next 10 km the whole area has been designated an archaeological park with normal traffic forbidden.

You may decide instead to buy a ticket for the 'Archeobus' (rather expensive - currently 12 euros - but it is valid for 48 hours; a joint deal exists together with the open-top 110 route for 25 euros); this starts from Termini station, with a stop in Piazza Venezia: it passes a good number of the important sights, and you can hop on and off ad lib; sadly though this no longer goes on through to the Parco degli Acquedotti (see below). If you have sufficient energy (and a reliably comfortable pair of shoes) you could take Metro Line A to the 'Giulio Agricola' station and walk the short distance to the Parco (a couple of buses travel even closer in if you go on a bit further to the 'Subaugusta' station - currently 451, 503 or 557),and then spend the rest of the day exploring as far up the old road as you want from there.

For other areas (e.g. the Parco della Caffarella) some of the other Metro stops are reasonably close (e.g. Colli Albani, Arco di Travertino),and a few of the outer bus-routes are also not far to walk from (see also the 218 bus mentioned above as a way to reach some of the catacombs).

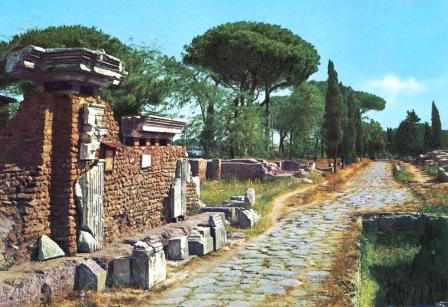

Historically, the Via Appia was built at the orders and expense of the famous Republican politician Appius Claudius ('the Blind') in 312 BC, as the main road to the south of Italy; it was so well-constructed and useful that it became known as the 'Queen of Roads'. Although inevitably the part closest to the city was eventually heavily built up, and a later highway, the Via Appia Nova, was constructed for modern use further on, the stretch of about 12 km in between is remarkably well-preserved, with some parts even retaining the huge ancient flagstones of its original surface. Only in recent years has any serious attempt been made to ensure its proper conservation, but with funds in particular laid aside at the Millennium, a pretty good job has so far been done - let's hope that future cut-backs don't allow it to revert to wasteland!

You can roughly divide it into four main areas of interest along the road (not counting the catacombs): the churches and monuments as far as S Sebastiano; the Parco della Caffarella, a little to the north of the first 2-mile section; the monuments of the main rural stretch of the Via Appia Antica - easily the largest and most interesting part; and the Parco degli Acquedotti. Here follows (if you are interested!) a brief description of each - I won't go into great detail however.

Firstly, passing under the so-called Arch of Drusus and leaving the old city through the Porta S Sebastiano on the traffic-laden modern road, you soon pass the first mile-stone, and then, near a small river (called the Almone),is the actual Park Office, where you can get information, hire bicycles etc.

A little further along on the left is the church of Domine Quo Vadis, marking the spot where St Peter, intending to abandon Rome during Nero's persecutions after the Great Fire in AD 64, is said to have seen a vision of Jesus walking back towards the city. In response to Peter's surprised question "Where are you going, Lord?" Jesus replied "If you are deserting my flock, I am going to Rome myself to be crucified a second time!" Immediately, Peter turned back - to meet his own fate, of course, in the Vatican Circus.

The scene is memorably portrayed in the 1950's Hollywood film version of Henryk Sienkiewicz's eponymous novel, with Finlay Currie as Peter (and a completely over-the-top Peter Ustinov as Nero…)

A cast, said to be of Christ's footprints, is preserved further on in S Sebastiano - although I have often wondered why it isn't kept in the church here!

Visible opposite the church is a structure known as the 'Tomb of Priscilla'.

The 218 Bus forks off to the right here (see the second movement),but the 118 continues along the now slightly less crowded road, past the Columbarium (burial complex - the word actually means 'dove-cote' in Latin) of the Freedmen of Augustus - the quirky restaurant here previously, where you could dine sitting out amongst the burial niches (the Hostaria Antica Roma) has unfortunately recently relocated to further along the road - but it is still very good! Next there is a stop for the side-entrance to the S Callisto catacombs. Just before reaching S Sebastiano the bus annoyingly turns left - from there on, the road is reserved for less frantic traffic.

To explore the attractive Parco della Caffarella, you can either approach from Domine Quo Vadis (a road leads to it off to the left),or stay on the bus here for one more stop and enter near the church of Sant'Urbano. This is actually a lot closer to the most interesting areas: a 'Bosco Sacro' (Sacred Grove) and the Nymphaeum of Egeria - the prophetic consort of King Numa are well worth seeing.

There are also more catacombs: those of 'the Jews', and of 'Praetextatus'; neither of these are easy to visit however. Further back towards the earlier entrance is what used to be oddly known as the 'Temple of the Deus Rediculus' - nothing either to do with laughter, nor what the name actually does mean: supposedly, the spot where a god intervened to make the invading Hannibal 'turn back/return', losing his nerve at the very gates of the city. It is now identified instead as a second-century tomb, belonging to the wife of Herodes Atticus, the millionaire Athenian philanthropist and man-of-letters who was a tutor to Marcus Aurelius. The park around here is quite delightful, and it is hard to believe you are so close to the city.

Further on, still to the north of the actual road, is another park, the Parco degli Acquedotti, adjoining the Villa Quintili, the home originally of two consular brothers of the second century who wrote studies on agriculture. They were put to death by the jealous and savage emperor Commodus, who coveted their estates for himself - there is no denying that they are very beautiful, with some resemblance in their architecture to Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli.

Across (or under!) the Via Appia Nuova, which stands in between, you can reach the Park of the Aqueducts - no less than seven traverse this equally delightful open space, both over and under the ground. It is a pity the park is not all that easy to get to (see transport suggestions above).

The most evocative and attractive part of the road, though, can be found in the 10-mile stretch from S Sebastiano onwards. This is where many of the most famous monuments stand, interspersed with and surrounded by the trees which Respighi depicts, standing vigil over the scenes that took place along its length (at least, in the poet's imagination) beneath them.

Here, first, are some of the remains of buildings by the late Emperor Maxentius: part of his villa, and a well-preserved Circus (where the obelisk which now forms the centrepiece of Bernini's "Fountain of the Four Rivers" in Piazza Navona was found),and a memorial tomb to his young son Romulus.

Then, perhaps the most iconic of all the monuments on the Appian Way, stands the round, castellated Tomb of Caecilia Metella, wife of Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Caesar's generals in Gaul, and son of the famous triumvir (whose name he shared) along with Pompey and Caesar: Crassus the elder, thanks to his penchant for buying up vacant property lots that had collapsed or been destroyed by fire at aptly 'knock-down' prices, became almost proverbial as the richest man in Rome of his time - no doubt some of this wealth was inherited by his son and put to good use with this tomb for his wife.

Its castellated crown is a legacy of the fortress it became in medieval times, having passed into the control of the noble Caetani family.

Not far on from here the 'archaeological park' begins in earnest, with many important and interesting monuments; it would be tedious just to give a list with no descriptions attached, so I can only suggest that if you want to know more about the Tomb of Seneca, the Tumuli of the Horatii and the Curiatii, the Casal Rotondo…(to name but a few of its treasures) you consult a reputable guide-book - or better still, go and explore yourself!

Once again, however, it is the memories and atmosphere evoked by the 'idea' of the Appian Way that forms the inspiration for Respighi's music. No one stretch of it needs to be identified to create for oneself a picture in the imagination, backed up by the various prompts and musical clues the composer provides. Indeed, his programme notes almost say it all; but the most help comes of course from what you hear.

When I was a schoolteacher, I occasionally used to play this movement to some of my classes, without any previous explanation, and ask them to draw a picture of what it suggested to them. More often than not, elements of Respighi's intentions came through: a parade of some type, a gradual sunrise, marching soldiers were recurrent results. I well remember too (if you will allow me to be completely personal for a moment) the first time I ever heard the music myself, as a boy of about 12: my parents were watching a TV concert (probably the Proms),and I was in my bedroom upstairs. Gradually I became aware of the persistent drumbeat from below and the trumpet fanfares getting louder and louder - I just had to drop what I was doing and run downstairs to listen properly and find out what it was. If this is "picture-postcard music", I for one can vouch for its success in taking me completely, in my mind, to the "place" it was "sent from"; and I have no doubt it was another moment that helped to confirm a deep feeling and love for the classical world - ancient then, and over the years its modern city descendant - which has been with me ever since as the main focus of my working life (not to mention holidays and retirement!) For me at least, few pieces of music are more successful in conjuring up the mood and emotions they hope to create.

From the very start, the march is announced with that insistent rhythmic beat on the timpani, quietly emerging from the mists before dawn - an eerie half-light evoked by low woodwind, taken up by almost sinister muted fanfares from the brass. A mournful sigh begins on the strings - above it the first half-statement of the main theme: the advancing army is escorting a column of miserable captives in chains….the cor anglais starts a sinuous eastern melody, deeply full of longing and regret: these troops are returning from afar, with a hoard of groaning slaves as the spoils of their victory.

The marching feet grow louder (a fine moment when the bass-drum joins the timpani accenting the first beat of each bar),and we hear a proper statement of the theme, on the trombones. They are answered by a muted fanfare on instruments described by Respighi as 'buccine' - the valve-less curved horn of the ancient legionaries, worn over the shoulder (not surprisingly, in most performances these are substituted by a separate bank of muted ordinary trumpets!) - it is almost as if the city outposts have spotted them, and are announcing their arrival to the expectant citizens…

From here, the beat of the march and the fanfares slowly and very effectively build in volume. Ever watched by the pines, the army draws closer to the city gates. The music is underpinned by deep pedal notes on the organ, and a long slowly-rising scale on the strings. In a good performance, the tempo of the march will not increase - sadly, too many recordings of the piece seem to speed up, until the soldiers are almost performing an unseemly "Olympic-walk"-style dash for the finishing-line! Avoiding this is one of the Kertesz recording's strong points.

Fanfare answers fanfare - the city's 'buccine' are all but drowned out by the blasts from the legion itself. As the victorious procession reaches the city, crowds line their way and cheers go up from street to street - imagine this from the successive key changes accented by cymbal crashes ….the column wheels to the right at the Circus Maximus…past the Colosseum and up under Titus's Arch: they reach the Forum…onto the ancient Sacred Way towards Capitol Hill crowned by the most holy temple of Jupiter, Best and Greatest…more trumpet fanfares: there is no hope of the city trumpeters matching the troops now!... the parade fills the Forum square below the rostra and halts….salutes between the victorious general and his Emperor…. The crowd erupts with an enormous cheer of pride and welcome.

And the Pines bear witness, as they have done many times before….

OK, this is rather a subjective interpretation, not to mention needing to fore-shorten the distances involved more than somewhat! But it is a measure of the effective picture-painting in sound achieved by Respighi that it is possible to build such a vivid scene in one's imagination. Uplifting, moving, majestic…it is one of those pieces which never fails to set the spine tingling.

The "Pines of Rome" very quickly became Respighi's most popular and most frequently performed composition - as it has remained to this day. He had developed quite a long way in terms of sonority and chromaticism since the "Fountains": but the final piece in the Trilogy was to take the spectacular effects of orchestration and variety of mood to even greater heights.

COMING SOON:

Other pieces connected with Rome

POSSIBLE ITINERARIES

A: Full route, keeping to the times-of-day in the music (as followed in the text)

1. Daybreak at Giulia Fountain

2. Villa Borghese Park

3. Galleria Borghese

4. 116 Bus to Piazza Barberini

5. Triton Fountain

6. Palazzo Barberini

7. Walk to Trevi Fountain

8. Lunch

9. Accademia di S Luca

10. Walk to Via dei Due Macelli

11. 117/119 to Piazza di Spagna

12. Via Vittoria: Conservatorio di S Cecilia

13. Corso/Via del Babuino to Piazza del Popolo

14. S Maria del Popolo

15. Piazza del Popolo to Pincio Hill

16. Villa Medici Fountain

B: (omits Galleria Borghese)

1. Daybreak at Giulia Fountain

2. Villa Borghese Park

3. 116 Bus to Piazza Barberini (c. 10.00 a.m.)

4. Palazzo Barberini (longer visit)

5. Trevi Fountain (12.00)

6. Lunch

Then as Itinerary A

C: (museums in different order)

1. Daybreak at Giulia Fountain

2. Villa Borghese Park

3. Galleria Borghese

4. Bus 116 to Piazza Barberini

5. Triton Fountain (11.00 a.m)

6. Accademia di S Luca

7. Trevi Fountain (12.00)

8. Lunch

9. Palazzo Barberini

10. Walk to Via dei Due Macelli

Then as Itinerary A

D: Simply visiting the Fountains (may include other Respighi 'locations' if desired) - no timings necessary

1. Arrive at Giulia Fountain

2. Bus 116 to Piazza Barberini and Triton Fountain

3. Walk to Trevi Fountain

4. Walk to Via dei Due Macelli

5. 117/119 to Piazza di Spagna

(If then to include S Cecilia and S Maria del Popolo see Itinerary A),or…

6. Climb Spanish Steps and turn up left to Villa Medici Fountain